Rampage (1987 film)

| Rampage | |

|---|---|

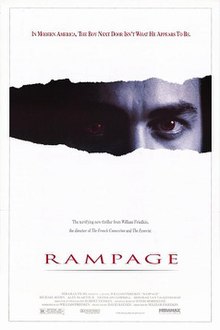

Promotional poster | |

| Directed by | William Friedkin |

| Screenplay by | William Friedkin |

| Based on | Rampage 1985 novel by William P. Wood |

| Produced by | William Friedkin David Salven |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Robert D. Yeoman |

| Edited by | Jere Huggins |

| Music by | Ennio Morricone |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Miramax Films |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 97 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $7.5 million[1][2] |

| Box office | $796,368[3] |

Rampage is a 1987 American crime drama film written, produced and directed by William Friedkin. The film stars Michael Biehn, Alex McArthur, and Nicholas Campbell. Friedkin wrote the script based on the novel of the same name by William P. Wood, which was inspired by the life of Richard Chase.[4]

The film premiered at the Boston Film Festival on September 24, 1987, but its theatrical release was stalled for five years due to production company and distributor De Laurentiis Entertainment Group going bankrupt. In 1992, Miramax obtained distribution rights and gave the film a limited release in North America. For the Miramax release, Friedkin reedited the film and changed the ending.

Plot summary

[edit]Charles Reece is a serial killer who commits a number of brutal mutilation-slayings in order to drink blood as a result of paranoid delusions. Reece is soon captured. Most of the film revolves around the trial and the prosecutor's attempts to have Reece found sane and given the death penalty. Defense lawyers, meanwhile, argue that the defendant is not guilty by reason of insanity. The prosecutor, Anthony Fraser, was previously against capital punishment, but he seeks such a penalty in the face of Reece's brutal crimes after meeting one victim's grieving family.

In the end, Reece is found sane and given the death penalty, but Fraser's internal debate about capital punishment is rendered academic when Reece is found to be insane by a scanning of his brain for mental illness. In the ending of the original version of the film, Reece is found dead in his cell, having overdosed himself on antipsychotics he had been stockpiling.

Alternate ending

[edit]In the ending of the revised version, Reece is sent to a state mental hospital, and in a chilling coda, he sends a letter to a person whose wife and child he has killed, asking the man to come and visit him. A final title card reveals that Reece is scheduled for a parole hearing in six months.

Cast

[edit]- Michael Biehn as Anthony Fraser

- Alex McArthur as Charlie Reece

- Nicholas Campbell as Albert Morse

- Deborah Van Valkenburgh as Kate Fraser

- John Harkins as Dr. Keddie

- Art LaFleur as Mel Sanderson

- Billy Greenbush as Judge McKinsey

- Royce D. Applegate as Gene Tippetts

- Grace Zabriskie as Naomi Reece

- Carlos Palomino as Nestode

- Roy London as Dr. Paul Rudin

- Donald Hotton as Dr. Leon Gables

- Andy Romano as Spencer Whaley

- Patrick Cronin as Harry Bellenger

- Whitby Hertford as Andrew Tippetts

- Brenda Lilly as Eileen Tippetts

- Roger Nolan as Dr. Roy Blair

- Rosalyn Marshall as Sally Ann

- Joseph Whipp as Dr. George Mahon

- Angelo Vitale as Assistant District Attorney

- Paul Gaddoni as Aaron Tippetts

Influences

[edit]Charles Reece is a composite of several serial killers,[5] and primarily based on Richard Chase. Chase committed his crimes in Sacramento, California during late 1977 and early 1978, rather than in Stockton, California during late 1986 like in Rampage.[6]

Reece's victims are slightly different from Chase's. Reece kills three women, a man and a young boy, whereas Chase killed two men, two women (one of whom was pregnant), a young boy and a 22-month-old baby. Additionally, Reece escapes at one point—which Chase did not do—murdering two guards and later a priest. However, Reece and Chase had a similar history of being institutionalized for mental illness prior to their murders, along with sharing a fascination with drinking blood. Their murders are both motivated by the belief that they need blood since their heart and internal organs are failing. The two had friends and girlfriends during their childhood/teen years, before descending into mental illness during early adulthood. The mental institution that Reece served at was called "Sunnyslope", whereas Chase's real life mental institution was called Beverly Manner.[7] Reece disposes of one of his child victims in a box inside a garbage bin, and it takes a long time for the police to find the decomposed corpse. This is directly inspired by Chase's murder of 22-month-old David Ferreira in January 1978. Ferreira was murdered along with his cousin, aunt and a male friend of his aunt, when Chase randomly entered their house. Chase took the baby's body to his apartment to decapitate it and consume the brains, later placing his corpse in a box in a garbage bin, which was not discovered by police until two months after Chase's arrest. When police search Reece's home, they discover brains there, but it isn't ever explicitly mentioned that Reece consumed the brains of the boy he murdered. During the mass murder at Ferreira's aunt's house, Chase cut open her organs, having also done this to a previous female victim whose house he entered when she was alone.[7] All of Chase's other victims were boys and men that he shot and didn't cut open like the women.[7] In Ramapge, it is said that Reece only cuts open the organs of his female victims, and that he just shoots the others.

Reece wears a bright colored ski parka during his murders and walks into the houses of his victims, as did Chase. The two also share the same paranoia about being poisoned. When Reece is incarcerated, he refuses to eat the prison food since he believes it has been poisoned, which mirrors the behavior of Chase in prison. who tried to get the food he was being served tested since he thought it was poisoned.[7][8] In the 1992 cut, Reece was potentially going to be paroled from a Californian mental health facility. He was sent to this facility when brain scans help prove his madness, after having originally been sentenced to death. Chase, on the other hand, was sentenced to death without the possibility of being freed, but before the sentence could be carried out overdosed on prescribed pills in his cell.[9][10] Chase's suicide occurred in San Quentin Prison in 1980, a few months after he had a brief stay in a facility for the criminally insane, which he was temporarily sent to after behaving psychotically during his first few months at San Quentin.[7] The original 1987 cut had Reece overdosing on pills, just before the brain scan results came in, which would have helped get his death sentence overturned. In the early 1990s, Friedkin said he didn't have Reece commit suicide in the second cut since having him be released from prison fitted better with the traditions of the United States.[11] In both versions of the film, Reece lives with his mother and has a job at a gas station. When Chase's crimes were being committed, he lived alone in an apartment and was unemployed. Reece's father is also said to have died when he was a child, whereas Chase's father was still alive when his crimes were being committed.

While Chase was noted for having an unkempt appearance and exhibiting traits of paranoid schizophrenia in public, the film's makers intended to portray Reece as "quietly insane, not visually crazed."[5] Alex McArthur said in 1992 that "Friedkin didn't want me to play the guy as a raging maniac. We tried to illustrate the fact that many serial killers are clean-cut, ordinary appearing men who don't look the part. They aren't hideous monsters."[5] To prepare for the role, Friedkin introduced McArthur to a psychiatrist who deals with schizophrenics. He showed McArthur video tapes of interviews with different serial killers and other schizoids.[5]

The incident where Reece goes on a rampage after escaping custody was inspired by a real-life event in Illinois, that occurred while the film was in production.[5] In this event, the killer painted his face silver, something which Reece also does.[5]

The film had a negative portrayal of courtroom experts, and this was personally motivated by Friedkin's ongoing custody battle for his son, which he was having with his ex-wife.[12]

Production and release

[edit]The 1985 novel the film was based on was written by William P. Wood, a Californian prosecutor involved with the 1979 trial of Richard Chase.[13][14] Wood sent the novel to Friedkin, who then decided to make a film about it.[13] In an October 1992 interview on Charlie Rose, Friedkin discussed the film, and said he wanted to create films "which concern themselves with the way we live now. [And] those issues that have a real edge to them, and are of vital concern to people." He added that, "I won't just want to make a film about four teenagers having sex in the back of a car, which is your average summer picture these days. I mostly want to make films that are dealing with ideas."[13] The issue of the death penalty is something which was close to Friedkin, as one of his earliest films was a documentary against the death penalty.[13]

In the Charlie Rose interview, Friedkin said actor Michael Biehn was the biggest name in Rampage, and that it didn't use a particularly well-known cast.[13] It was filmed in late 1986 in Stockton, California, where it had a one day only fundraising premiere at the Stockton Royal Theaters in August 1987. It played at the Boston Film Festival in September 1987, and ran theatrically in some European countries in the late 1980s. Plans for the film's theatrical release in America were shelved when production studio DEG, the distributor of Rampage, went bankrupt. The film was unreleased in North America for five years.[15] During that time, director Friedkin reedited the film, and changed the ending (with Reece no longer committing suicide in jail) before its US release in October 1992.[2][16] The European video versions usually feature the film's original ending. The original cut of the film has a 1987 copyright date in the credits, while the later cut has a 1992 copyright date, and includes new distributor Miramax's logo at the beginning, instead of DEG's. The original cut also has the standard disclaimer in the credits about the events and characters being fictitious, unlike the later cut, which has a customized disclaimer, mentioning that it was partly inspired by real events.

In retrospective 2013 interview, Friedkin said: "at the time we made Rampage, [producer] Dino De Laurentiis was running out of money. He finally went bankrupt, after a long career as a producer. He was doing just scores of films and was unable to give any of them his real support and effort. And so literally by the time it came to release Rampage, he didn’t have the money to do it. And he was not only the financier, but the distributor. His company went bankrupt, and the film went to black for about five years. Eventually, the Weinsteins' company Miramax took it out of bankruptcy and rereleased it. But this was among the lowest points in my career."[17] There was a year long negotiation with Miramax, and a disappointing test screening of the original cut. The changes that Friedkin made with the 1992 cut addressed concerns from Miramax that the film was not coherent enough, in addition to addressing Friedkin's changing stance towards the death penalty.[12] The 1992 cut included a previously unreleased scene of Reece buying a handgun at the beginning and lying about his history of mental illness (just as Richard Chase did), whereas the original cut begins with one of Reece's murders, without explaining any of his background.

Regarding the five year gap between the film's American release, McArthur said in 1992: "It was a weird experience. First it was coming out and then it wasn't, back and forth. The fact that it was released at all is amazing." McArthur added that: "I've changed a lot since that picture was made. I have three children now and I'm not sure I would play the part today. I certainly wouldn't want my kids to see it."[5]

Beginning on October 30, 1992, the film played at 175 theaters in the United States, grossing roughly half a million dollars against a budget of several million dollars.[18] McArthur said in 1992 that the film was never intended to be a big commercial hit.[5]

Soundtrack

[edit]The film's score was composed, orchestrated, arranged and conducted by Ennio Morricone and was released on vinyl LP, cassette and compact disc by Virgin Records.[19]

Reception

[edit]The film received a polarized response.[20][21] Some critics ranked Rampage among Friedkin's best work.[2] In his review, film critic Roger Ebert gave Rampage three stars out of four, saying: "This is not a movie about murder so much as a movie about insanity—as it applies to murder in modern American criminal courts...Friedkin['s] message is clear: Those who commit heinous crimes should pay for them, sane or insane. You kill somebody, you fry—unless the verdict is murky or there were extenuating circumstances."[22] Janet Maslin of The New York Times praised the acting and commented: "Rampage has a no-frills, realistic look that serves its subject well, and it avoids an exploitative tone."[23]

Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly called the film "despicable", saying that the "movie devolves into hateful propaganda" and "its muddled legal arguments come off as cover for a kind of righteous blood lust".[24] Stephen King, an admirer of Rampage, wrote a letter to the magazine defending the film.[2]

Desson Howard of The Washington Post noted that in the film's five year delay, there had been several high profile serial killer cases, saying: "In this Jeffrey Dahmer era, McArthur's claims of unseen voices and delusions that he needed to replace his contaminated blood with others' are familiar tabloid fare", however, he noted that despite this, the film "still preserves a horrifying edge."[25] In a separate 1992 review for The Washington Post, Richard Harrington had a more negative view, criticizing the film for feeling like a made for television feature, and claiming that it had a dated look to it due to its long delay.[26] Gene Siskel believed the only reason the film was getting an American theatrical release after five years was because of the success of the 1991 serial killer film The Silence of the Lambs, saying THAT Rampage's subjects "may be fascinating but are hardly commercial, particularly when the killings are so gruesome." He also characterized it as having less of a "glamorous" portrayal of serial killers than The Silence of the Lambs, and believed the film would have been stronger if it focused more on the court room aspects and cut out the murder scenes.[27][28]

In retrospect, William Friedkin said: "There are a lot of people who [now] love Rampage, but I don’t think I hit my own mark with that".[17] In another interview, Friedkin said he thought the film failed because audiences perceived it as being too serious, and they were expecting something different from him.[12]

In 2021, Patrick Jankiewicz of Fangoria wrote: "Half-serial killer thriller, half-courtroom drama, Rampage is an unnerving study on the nature of evil and what society should do about it."[29]

Home media

[edit]Friedkin's original cut featuring the alternate ending and some additional footage was released on LaserDisc in Japan only by Shochiku Home Video in 1990.[2]

The American edit of the film was released on LaserDisc in 1994 by Paramount Home Video.[2] The film received a DVD release by SPI International in Poland.[30]

In December 2023, Kino Lorber announced plans to release Rampage in 4K UHD in 2024.[31] As of 2025, the release has still not occurred yet for unspecified reasons.

References

[edit]- ^ Knoedelseder Jr., William K. (August 30, 1987). "Producer's Picture Darkens". Los Angeles Times. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f Kelley, Bill (December 6, 1992). "Delayed 'Rampage' a "New" Serial Killer Film is Actually a Re-Cut Version of a Movie Shelved for Six Years". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ Rampage at Box Office Mojo

- ^ Liebenson, Donald (June 18, 1993). "But Soft, Friedkin Speaks". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 30, 2023. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Alex McArthur starred in 'Rampage' five years ago and... - UPI Archives".

- ^ "The Vampire of Sacramento Richard Trenton Chase". Haunted America Tours. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Sullivan, Kevin (2012). Vampire: The Richard Chase Murders. WildBlue Press. ISBN 978-1942266112.

- ^ Ressler, Robert; Thomas Schachtman (1992). Whoever Fights Monsters: My Twenty Years Tracking Serial Killers for the FBI (First ed.). St. Martin's. p. 14. ISBN 0-312-07883-8.

- ^ "Richard Trenton Chase - Crime Library". truTV.com. Archived from the original on February 28, 2009. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- ^ Friedkin 2013, pp. 396–401.

- ^ "Richard Chase". groups.google.com.

- ^ a b c Horn, D. C. (2023). The Lost Decade: Altman, Coppola, Friedkin and the Hollywood Renaissance Auteur in the 1980s. United States: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- ^ a b c d e 1992 William Friedkin interview. Charlie Rose [1]

- ^ "About | Author William P. Wood".

- ^ "Friedkin vs. Friedkin: RAMPAGE Revisited". Video Watchdog. No. 13. September 1992. p. 36.

- ^ Friedkin 2013, pp. 400–401.

- ^ a b Ebiri, Bilge (May 3, 2013). "Director William Friedkin on Rising and Falling and Rising in the Film Industry". Vulture. Archived from the original on May 5, 2013.

- ^ "Rampage (1992) - Financial Information". The Numbers.

- ^ "Ennio Morricone – Rampage (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack)". Discogs. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ Dry, Sarah C. (October 29, 2002). "AN EYE FOR AN EYE: "Rampage" Shows the Horror of Murder". The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ Terry, Clifford (October 30, 1992). "From mad to worse". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 30, 2023. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (October 30, 1992). "Rampage". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 28, 2017 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (October 30, 1992). "Review/Film; Random Murder Spree In a Friedkin Thriller". The New York Times. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (November 6, 1992). "Rampage (1992)". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 20, 2007. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ Desson Howe (October 30, 1992). "'Rampage' (R)". The Washington Post.

- ^ Richard Harrington (October 30, 1992). "'Rampage' (R)". The Washington Post.

- ^ https://www.nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=gcp19921105-01.1.32&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN----------

- ^ Siskel, Gene (October 30, 1992). "Friedkin's 'Rampage' Skims Surface of Provocative Subject". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 30, 2023. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ Jankiewicz, Patrick (April 28, 2021). "William Friedkin's RAMPAGE: How An Underrated Modern Serial Killer Thriller Was Lost And Found". Fangoria. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ "Rampage (DVD) Michael Biehn McArthur William Friedkin PL IMPORT". Amazon. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

- ^ Hamman, Cody (December 28, 2023). "Rampage: William Friedkin serial killer thriller is getting a 4K UHD release". JoBlo.com. Retrieved December 30, 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Friedkin, William (2013). The Friedkin Connection: A Memoir. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0061775123.

External links

[edit]- 1987 films

- 1987 crime drama films

- 1987 crime thriller films

- 1987 independent films

- American courtroom films

- American crime drama films

- American crime thriller films

- American films based on plays

- American independent films

- Films about cannibalism

- De Laurentiis Entertainment Group films

- 1980s English-language films

- 1980s legal drama films

- 1980s serial killer films

- Films based on American novels

- Films directed by William Friedkin

- Films scored by Ennio Morricone

- Films shot in California

- Films about mental health

- American serial killer films

- 1980s American films

- English-language crime drama films

- English-language independent films

- English-language crime thriller films