Papermaking

Papermaking is the manufacture of paper and cardboard, which are used widely for printing, writing, and packaging, among many other purposes. Today almost all paper is made using industrial machinery, while handmade paper survives as a specialized craft and a medium for artistic expression.

In papermaking, a dilute suspension consisting mostly of separate cellulose fibres in water is drained through a sieve-like screen, so that a mat of randomly interwoven fibres is laid down. Water is further removed from this sheet by pressing, sometimes aided by suction or vacuum, or heating. Once dry, a generally flat, uniform and strong sheet of paper is achieved.

Before the invention and current widespread adoption of automated machinery, all paper was made by hand, formed or laid one sheet at a time by specialized laborers. Even today those who make paper by hand use tools and technologies quite similar to those existing hundreds of years ago, as originally developed in China and other regions of Asia, or those further modified in Europe. Handmade paper is still appreciated for its distinctive uniqueness and the skilled craft involved in making each sheet, in contrast with the higher degree of uniformity and perfection at lower prices achieved among industrial products.

History

[edit]The word "paper" is etymologically derived from papyrus, Ancient Greek for the Cyperus papyrus plant. Papyrus is a thick, paper-like material produced from the pith of the Cyperus papyrus plant which was used in ancient Egypt and other Mediterranean societies for writing long before paper was used in China.[1] Papyrus is prepared by cutting off thin ribbon-like strips of the pith (interior) of the Cyperus papyrus plant and then laying out the strips side-by-side to make a sheet. A second layer is then placed on top, with the strips running perpendicular to the first. The two layers are then pounded together using a mallet to make a sheet. The result is very strong, but has an uneven surface, especially at the edges of the strips. When used in scrolls, repeated rolling and unrolling causes the strips to come apart again, typically along vertical lines. This effect can be seen in many ancient papyrus documents.[2]

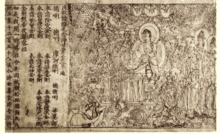

Hemp paper had been used in China for wrapping and padding since the eighth century BC.[3] Paper with legible Chinese writings on it has been dated to 8 BC.[4] The traditional inventor attribution is of Cai Lun, an official attached to the Imperial court during the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 CE), said to have invented paper about 105 CE using mulberry and other bast fibres along with fishnets, old rags, and hemp waste.[5] Paper used as a writing medium had become widespread by the 3rd century[6] and, by the 6th century, toilet paper was starting to be used in China as well.[7] During the Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) paper was folded and sewn into square bags to preserve the flavour of tea,[3] while the later Song dynasty (960–1279 CE) was the first government to issue paper-printed money.

In the 8th century, papermaking spread to the Islamic world, where the process was refined, and machinery was designed for bulk manufacturing. Production began in Samarkand, Baghdad, Damascus, Cairo, Morocco, and then Muslim Spain.[8] In Baghdad, papermaking was under the supervision of the Grand Vizier Ja'far ibn Yahya. Muslims invented a method to make a thicker sheet of paper. This innovation helped transform papermaking from an art into a major industry.[9][8] The earliest use of water-powered mills in paper production, specifically the use of pulp mills for preparing the pulp for papermaking, dates back to Samarkand in the 8th century.[10] The earliest references to paper mills also come from the medieval Islamic world, where they were first noted in the 9th century by Arabic geographers in Damascus.[11]

Traditional papermaking in Asia uses the inner bark fibers of plants. This fiber is soaked, cooked, rinsed and traditionally hand-beaten to form the paper pulp. The long fibers are layered to form strong, translucent sheets of paper. In Eastern Asia, three traditional fibers are abaca, kōzo and gampi. In the Himalayas, paper is made from the lokta plant.[12] This paper is used for calligraphy, printing, book arts, and three-dimensional work, including origami. In other Southeast Asian countries, elephants are fed with large amount of starch food, so that their feces can be used to make paper as well. This can be found in elephant preservation camps in Myanmar, where the paper is sold to fund the organization's operations.[citation needed]

In Europe, papermaking moulds using metallic wire were developed, and features like the watermark were well established by 1300 CE, while hemp and linen rags were the main source of pulp, cotton eventually taking over after Southern plantations made that product in large quantities.[12] Papermaking was originally not popular in Europe due to not having many advantages over papyrus and parchment. It was not until the 15th century with the invention of the movable type of printing and its demand for paper that many paper mills entered production, and papermaking became an industry.[13][14]

Modern papermaking began in the early 19th century in Europe with the development of the Fourdrinier machine. This machine produces a continuous roll of paper rather than individual sheets. These machines are large. Some produce paper 150 meters in length and 10 meters wide. They can produce paper at a rate of 100 km/h. In 1844, Canadian Charles Fenerty and German Friedrich Gottlob Keller had invented the machine and associated process to make use of wood pulp in papermaking.[15] This innovation ended the nearly 2,000-year use of pulped rags and start a new era for the production of newsprint and eventually almost all paper was made out of pulped wood.

Manual

[edit]Papermaking, regardless of the scale on which it is done, involves making a dilute suspension of fibres in water, called "furnish", and forcing this suspension to drain through a screen, to produce a mat of interwoven fibres. Water is removed from this mat of fibres using a press.[17]

The method of manual papermaking changed very little over time, despite advances in technologies. The process of manufacturing handmade paper can be generalized into five steps:

- Separating the useful fibre from the rest of raw materials. (e.g. cellulose from wood, cotton, etc.)

- Beating down the fibre into pulp

- Adjusting the colour, mechanical, chemical, biological, and other properties of the paper by adding special chemical premixes

- Screening the resulting solution

- Pressing and drying to get the actual paper

Screening the fibre involves using a mesh made from non-corroding and inert material, such as brass, stainless steel or a synthetic fibre, which is stretched in a paper mould, a wooden frame similar to that of a window. The size of the paper is governed by the open area of the frame. The mould is then completely submerged in the furnish, then pulled, shaken and drained, forming a uniform coating on the screen. Excess water is then removed, the wet mat of fibre laid on top of a damp cloth or felt in a process called "couching". The process is repeated for the required number of sheets. This stack of wet mats is then pressed in a hydraulic press. The fairly damp fibre is then dried using a variety of methods, such as vacuum drying or simply air drying. Sometimes, the individual sheet is rolled to flatten, harden, and refine the surface. Finally, the paper is then cut to the desired shape or the standard shape (A4, letter, legal, etc.) and packed.[18][19]

The wooden frame is called a "deckle". The deckle leaves the edges of the paper slightly irregular and wavy, called "deckle edges", one of the indications that the paper was made by hand. Deckle-edged paper is occasionally mechanically imitated today to create the impression of old-fashioned luxury. The impressions in paper caused by the wires in the screen that run sideways are called "laid lines" and the impressions made, usually from top to bottom, by the wires holding the sideways wires together are called "chain lines". Watermarks are created by weaving a design into the wires in the mould. Handmade paper generally folds and tears more evenly along the laid lines.

The International Association of Hand Papermakers and Paper Artists (IAPMA) is the world-leading association for handmade paper artists.

Handmade paper is also prepared in laboratories to study papermaking and in paper mills to check the quality of the production process. The "handsheets" made according to TAPPI Standard T 205 [20] are circular sheets 15.9 cm (6.25 in) in diameter and are tested for paper characteristics such as brightness, strength and degree of sizing.[21] Paper made from other fibers, cotton being the most common, tends to be valued higher than wood-based paper.[citation needed]

Industrial

[edit]

A modern paper mill[when?] is divided into several sections, roughly corresponding to the processes involved in making handmade paper. Pulp is refined and mixed in water with other additives to make a pulp slurry. The head-box of the paper machine called Fourdrinier machine distributes the slurry onto a moving continuous screen, water drains from the slurry by gravity or under vacuum, the wet paper sheet goes through presses and dries, and finally rolls into large rolls. The outcome often weighs several tons.[citation needed]

Another type of paper machine, invented by John Dickinson in 1809, makes use of a cylinder mould that rotates while partially immersed in a vat of dilute pulp. The pulp is picked up by the wire mesh and covers the mould as it rises out of the vat. A couch roller is pressed against the mould to smooth out the pulp, and picks the wet sheet off the mould.[22][23]

Papermaking continues to be of concern from an environmental perspective, due to its use of harsh chemicals, its need for large amounts of water, and the resulting contamination risks, as well as the carbon sequestration lost by deforestation caused by clearcutting the trees used as the primary source of wood pulp.[citation needed]

Notable papermakers

[edit]While papermaking was considered a lifework, exclusive profession for most of its history, the term "notable papermakers" is often not strictly limited to those who actually make paper. Especially in the hand papermaking field there is currently an overlap of certain celebrated paper art practitioners with their other artistic pursuits, while in academia the term may be applied to those conducting research, education, or conservation of books and paper artifacts. In the industrial field it tends to overlap with science, technology and engineering, and often with management of the pulp and paper business itself.

Some well-known and recognized papermakers have found fame in other fields, to the point that their papermaking background is almost forgotten. One of the most notable examples might be that of the first humans that achieved flight, the Montgolfier brothers, where many accounts barely mention the paper mill their family owned, although paper used in their balloons did play a relevant role in their success, as probably did their familiarity with this light and strong material.

Key inventors include James Whatman, Henry Fourdrinier, Heinrich Voelter and Carl Daniel Ekman, among others.

By the mid-19th century, making paper by hand was extinct in the United States.[24] By 1912, fine book printer and publisher, Dard Hunter had reestablished the craft of fine hand paper making but by the 1930s the craft had lapsed in interest again.[24] When artist Douglass Howell returned to New York City after serving in World War II, he established himself as a fine art printmaker and discovered that art paper was in short supply.[24] During the 1940s and 1950s, Howell started reading Hunter's books on paper making, as well as he learned about hand paper making history, conducted paper making research, and learned about printed books.[25][26]

See also

[edit]- Amate, paper made of bark, used in pre-Columbian Central America

- Bookbinding

- Museums: Williams Paper Museum, Basel Paper Mill

- Stickies (papermaking)

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ "Papyrus definition". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2008-11-20.

- ^ Tsien 1985, p. 38

- ^ a b Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Part 1. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. Volume 5, p. 122.

- ^ "World Archaeological Congress eNewsletter 11 August 2006" (PDF).

- ^ Papermaking. (2007). In: Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 9, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Part 1. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. Volume 5, p. 1.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Part 1. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. Volume 5, p. 123.

- ^ a b Mahdavi, Farid (2003). "Review: Paper Before Print: The History and Impact of Paper in the Islamic World by Jonathan M. Bloom". Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 34 (1). MIT Press: 129–30. doi:10.1162/002219503322645899. S2CID 142232828.

- ^ Loveday, Helen. Islamic paper: a study of the ancient craft. Archetype Publications, 2001.

- ^ Lucas, Adam (2006). Wind, Water, Work: Ancient and Medieval Milling Technology. Brill Publishers. pp. 65 & 84. ISBN 90-04-14649-0.

- ^ Jonathan M. Bloom (February 12, 2010). "Paper in the Medieval Mediterranean World" (PDF). Early Paper: Techniques and Transmission – A workshop at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) [dead link] - ^ a b *Hunter, Dard (1978) [1st. pub. Alfred A. Knopf:1947]. Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-23619-6.

- ^ "The Atlas of Early Printing". atlas.lib.uiowa.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-02-15. Retrieved 2018-02-23.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Part 1. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. Volume 5, p. 4.

- ^ Burger, Peter. Charles Fenerty and his Paper Invention. Toronto: Peter Burger, 2007. ISBN 978-0-9783318-1-8 pp. 25–30

- ^ 香港臨時市政局 [Provisional Urban Council]; 中國歷史博物館聯合主辦 [Hong Kong Museum of History] (1998). "Zàozhǐ" 造纸 [Papermaking]. Tian gong kai wu: Zhongguo gu dai ke ji wen wu zhan 天工開物 中國古代科技文物展 [Heavenly Creations: Gems of Ancient Chinese Inventions] (in Chinese and English). Hong Kong: 香港歷史博物館 [Hong Kong Museum of History]. p. 60. ISBN 978-962-7039-37-2. OCLC 41895821.

- ^ Rudolf Patt; et al. (2005). "Paper and Pulp". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/1435369762/quest7.a18_545.pub4 (inactive 1 November 2024).

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ "Making Paper By Hand". TAPPI. Archived from the original on April 24, 2015. Retrieved 2016-04-30.

- ^ "Papermaking by Hand at Hayle Mill, England in 1976" Film by Anglia TV. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xs3PfwOItto

- ^ "Forming Handsheets for Physical Tests of Pulp" (PDF). TAPPI. Retrieved 2016-04-30.

- ^ Biermann, Christopher J. (1993). Handbook of Pulping and Papermaking. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-097360-X.

- ^ Paper Machine Clothing: Key to the Paper Making Process Sabit Adanur, Asten, CRC Press, 1997, pp. 120–136, ISBN 978-1-56676-544-2

- ^ "Cylinder machine device". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-04-05.

- ^ a b c "Douglas Morse Howell, Papermaking Champion". North American Hand Papermakers. Retrieved 2021-02-05.

- ^ Schreyer, Alice D. (1988). East-West, Hand Papermaking Traditions and Innovations: An Exhibition Catalogue. University of Delaware Library. Hugh M. Morris Library, University of Delaware Library.

- ^ Weber, Therese (2009). The Language of Paper: A History of 2000 Years. Marshall Cavendish Editions. p. 65. ISBN 978-981-261-628-9.

24. Longwood L.C. "Science and practice of hand made paper": (2004). 25. Westerlund L.C. "Fibre options for the sustainable development of the Australian Paper and Pulp Industry": (2004)

External links

[edit]- The Harrison Elliott Collection at the Library of Congress has paper specimens, personal papers and research material relating to the history of papermaking

- The Center for Book and Paper Arts at Columbia College Chicago hosted an exhibition on the contemporary art of hand papermaking in 2014

- The International Association of Hand Papermakers and Paper Artists (IAPMA)

- The Arnold Yates Paper collection at University of Maryland Libraries

- How to make a Carton: history of paper making in Australia, John Oxley Library blog